We're Free! Escaping Closed-Loop Cinema

Can you hear the music?

The first thing he notices is the violin.

Ryusuke Hamaguchi, the new poster boy of Japanese cinema, has had a quiet few months. After releasing two acclaimed films in 2021, he has spent the time since in rest mode. Creatively, his cup has run dry.

His eyes are closed. The open windows invite a crisp breeze. Birds whistle outside; a nearby spring gurgles gently.

Eiko Ishibashi, composer on his last film, fiddles at a production desk. She’s asked him to create a visual accompaniment to her latest composition. They’re in her studio.

Those strings. Desperate, pleading. Violent.

Ideas begin to come. Images. Tree trunks emerging from the snow.

Weeks pass, and the ideas keep coming. Then a script. Then a budget. Then a film.

Several months later, Hamaguchi’s unnerving, glass-like eco-parable Evil Does Not Exist (2024) is released.1 Cold but moving, it mirrors the beautiful violence of Ishibashi’s score, a quality that, in Hamaguchi’s words, “doesn’t allow you to feel safe.” Like its inspiration/soundtrack, its structure is sinewy, uneasy, discordant.

In other words, it rocks.

A rare example of a film inspired by its own soundtrack, Evil Does Not Exist feels so unique because it emerged from something outside itself. Its primary reference exists outside of film.

This is what open-loop cinema looks like.

I wrote last time about closed-loop cinema - a batch of 2024 movies whose identities are inextricably linked to other movies, rather than the world beyond the screen:

“However good they are - and some truly are great - these movies are strict subsets of earlier films. Their ambitions feel constrained, their identities small. This closed-loop cinema feels oddly hermetic: cinema as Narcissus, obsessed with its own reflection.”

All movies are inspired by older movies - true originality is a myth, etc. But closed-loop cinema blurs the line between emulation and inspiration. There is a difference between Mean Streets, which builds on the language of Cassavetes and Godard to become its own thing, and Alto Knights, which is a pale imitation of Scorsese.

Hamaguchi is a self-professed cinephile. His love of Rohmer, Cassavetes, and the like bleeds through his films. He cited Godard as an influence for Evil Does Not Exist. But - here’s the key point - the film is not a Godard retread. Far from it. It forges its own identity.

I’ve been reading Masters of Light, an interview series with various 1970s New Hollywood cinematographers. It’s striking how often their inspirations came from other art forms:2

Néstor Alemondros took cues from David Hockney, whose use of contemporary objects like cacti, lampshades, and chairs inspired Kramer vs. Kramer’s modern aesthetic.

John Bailey studied Italian fashion magazines for American Gigolo, reviving traditional Hollywood hard lighting, at the time out of vogue, instead of the soft, pastel lighting then commonly used.

Contrary to convention, Chinatown and Scarface cameraman John Alonzo didn’t care about source lighting — he noted that Rembrandt paintings never had source light, so why should he?

Mario Tosi bathed Carrie’s film’s climax in warm red light reminiscent of an old painting he’d seen of St Sebastian.

Vilmos Zsigmond and Robert Altman worked through an Andrew Wyeth book to develop the soft pastel imagery they used for McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

Think too about Indiana Jones, which was based on the old adventure serials of the 40s, or Apocalypse Now, which was inspired by the hallucinogenic weirdness of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, or the Phantom Thread, which Paul Thomas Anderson wrote after reading about Balenciaga.

Or, for a more recent example, look at this year’s Sinners, directed by Ryan Coogler. At first glance, this could be mistaken for a closed-loop film. It mirrors From Dusk Till Dawn’s structure and contains multiple other nods to the vampire canon. But this is a misread. The film stands on its own. It builds from its ancestors rather than bows to them. Why? Because, like Evil Does Not Exist, it takes its inspiration from beyond cinema. Blues, Irish folk, and death metal pulse through every frame. Its centrepiece sequence was born from the blues: “When I got to that moment of Sammie playing the blues, that’s when it hit me that I had to do this,” said Coogler. “I had to express, in a way that only film language can express.”

Openness to artistic life beyond cinema allows a film to tap into something higher. “We are at the present moment because of all the work that has been done up to now,” says Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro. “There is no question that when you make a design, shoot a picture or photograph a movie, it is the representation of all two thousand years of history.” Without that openness, filmmakers start halfway down the tube, drawing only on material that has already been filtered. At best, the end result is a remix; a cover album. One step removed from the Source.

Now we get to the painful bit. An uncomfortable truth for movie nerds like us: it is dangerously easy to obsess over films at the expense of other art forms.

How many books have the people who log 1000 films a year on Letterboxd read? How many galleries have they visited? How many plays have they seen?

Cinema culture has become painfully movie-brained. When we only watch movies, they begin to remind us only of other movies.

If we are to understand cinema as an art form - as a mirror to life - we need to tap into an artistic life beyond the screen. We need to start breaking the loop.

So, yes, maybe we need to watch fewer movies.

In fact, maybe we need to follow the lesson of one J. Robert Oppenheimer…

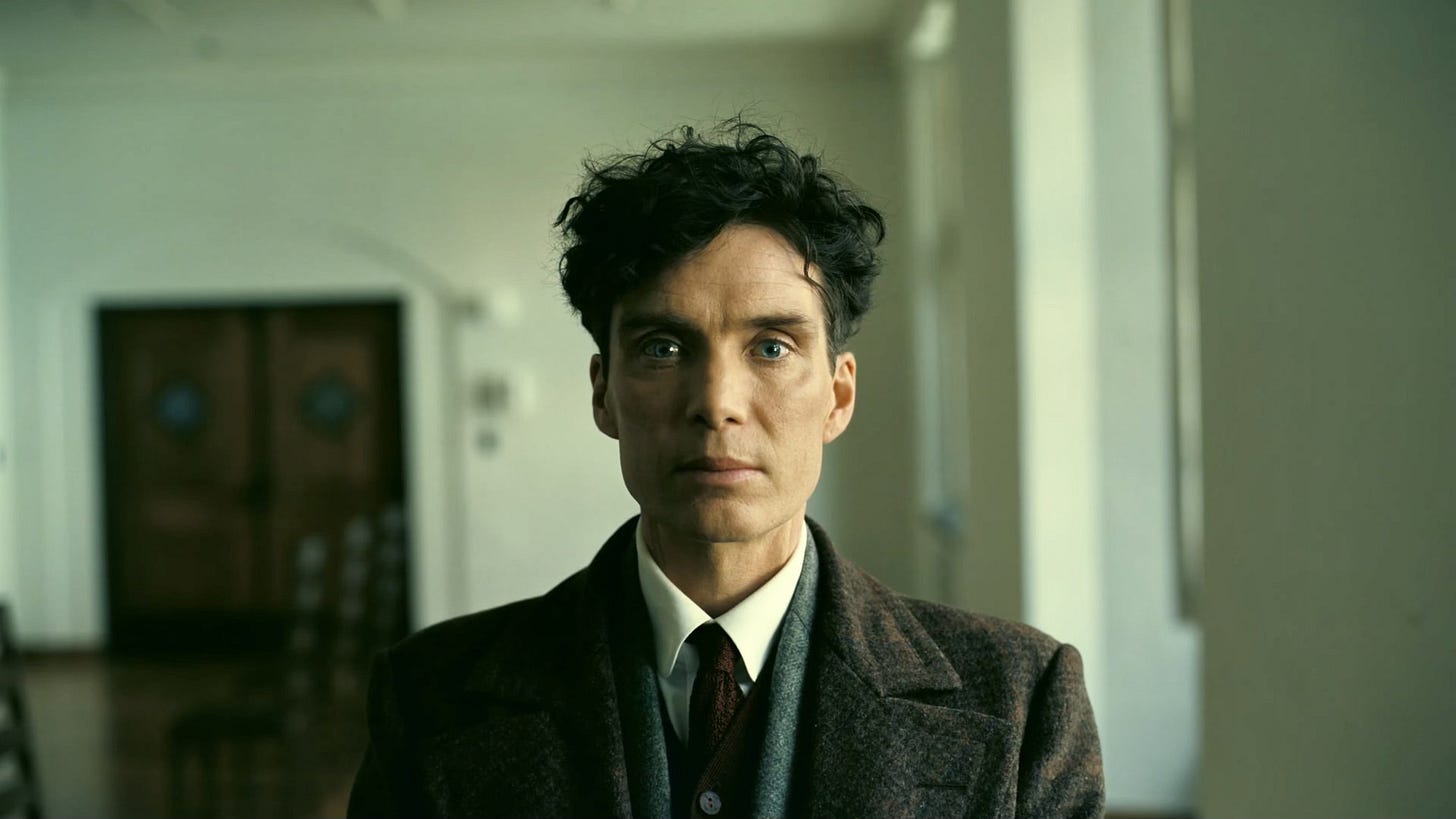

In the early moments of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, we see that the titular protagonist is haunted by a world shifting beneath his feet. At night, he hears whispers of changes beyond his comprehension. By day, he is trapped in the stuffy halls of Cambridge, grinding through equations without a breakthrough.

He is at the dawn of quantum physics, but he cannot yet see the sunrise.

Then, he meets Niels Bohr.

“Algebra is like a sheet of music,” Bohr tells him. “The important thing isn’t can you read music, it’s can you hear it.”

The implication is clear. Oppenheimer is thinking too technically, too narrowly. He must widen his influences.

In the subsequent montage, Oppenheimer sees a Picasso, he listens to Stravinsky, he reads T.S. Eliot. He travels. He visits the gothic majesty of a cathedral, light breaking through the stained glass. A creative breakthrough emerges. He sees the world in a new way. His understanding of quantum mechanics deepens precisely because he steps outside the scientific establishment.

Like Oppenheimer, perhaps we - filmmakers and fans alike - need to pay more attention to the music beyond the screen.

Can you hear it?

These posts take time. If you've enjoyed my work and would like to support it, please consider buying me a 'coffee'. I enjoy writing in coffee shops, so you would quite literally be fuelling my next piece!

I’ve taken some dramatic licence here based on this interview.

As luck would have it, as I was writing this piece, Cole Haddon published a great roundup of filmmakers who were inspired by fine art. Check it out!

Art is a process for understanding life better. It's a way of seeing the world. Those who see more create more artfully. For those wanting to expand their ways of seeing I really recommend the book "Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain" by Betty Edwards. This is the book that every employee at Pixar is required to read whether they are an animator or a janitor.

Fire article :)