We're Trapped! Welcome to Closed-Loop Cinema

Movies are becoming obsessed with their own reflection

Welcome, friends. Today is a day for problems, not solutions. There was a whole second half to this piece that I have GUILLOTINED, to be dealt with in my next post. As a result, the below came out a little saltier than expected. 🧂🧂Movies tend to be inspired by other movies. (Shocking, I know!)

Listen to any filmmaker talk about their latest release, and one of the first things they’ll do is reel off a list of films with similar DNA.1

The dialogue between filmmakers across generations is one of cinema's great excitements. To see echoes of Hal Ashby in A Real Pain (2024) or David Lynch in The Beast (2024) is to collapse decades of history in a way that only art can.

But lately, something feels off. The line between inspiration and emulation is beginning to blur. We’ve seen a splurge of films that feel trapped by their ancestors, obsessed with what came before.

2024 was a year of closed-loop cinema: movies whose identities depend on their relationship to other films, rather than to the world beyond the screen.

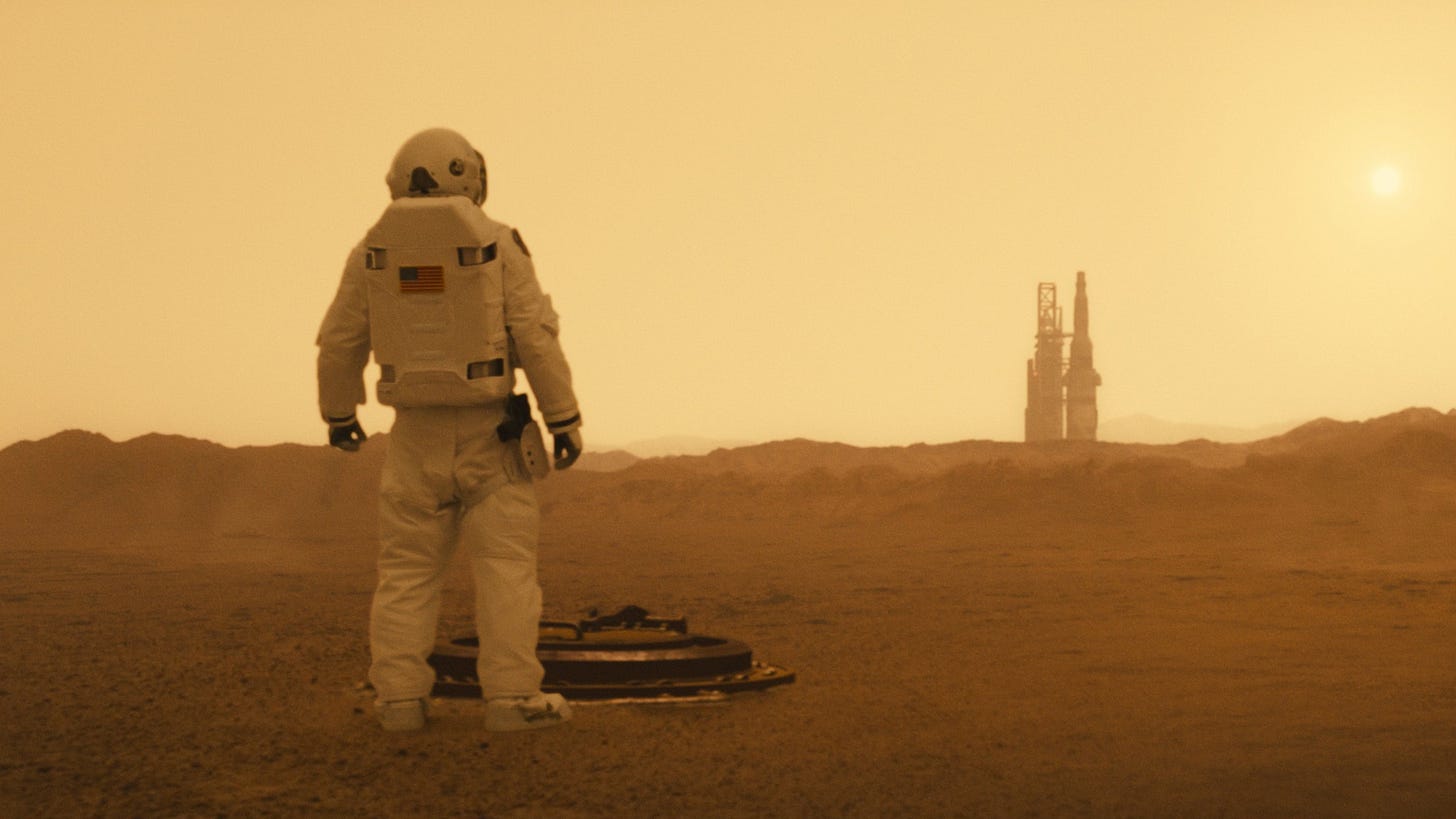

Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) emerged from the disturbing paintings of Swiss artist H.R. Giger. Fede Alvarez’s Alien: Romulus (2024) draws from… Alien.

George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977) was inspired by Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Wes Ball’s Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (2024) takes that same archetype but feels like… watered-down Star Wars.

Gladiator (2000) was born back in the 1970s during a motorcycle trip in Eastern Europe, when writer David Franzoni was overawed by the decaying grandeur of ancient ruins. Gladiator 2 gives us… more Gladiator.

What’s going on?

If you’re thinking, “Sequel culture strikes again!” - hold up! It’s not just franchise fare. Even in independent and auteur cinema, there’s a creeping sense of insularity.

Longlegs (2024) unashamedly evokes Silence of the Lambs (1991) (until it doesn’t…). The Substance (2024) is a Cronenberg retread. Monkey Man (2024) outright namedrops the John Wick franchise (while aping its neon-cool aesthetic). Maxxxine (2024) can be summarised, in the words of a commentator whose name I’ve forgotten, as “I too have seen the films of Brian de Palma.”

Don’t worry, this isn’t an “everything sucks now” diatribe (yawn). Many of these films ARE doing something new with their inspirations. But even when they tweak their source texts, their identities remain inextricably linked. The smart twist that Longlegs delivers in its final act only really lands because of how it subverts Silence of the Lambs. Even some of last year’s best films - the Oscar-winning Anora and my beloved A Different Man - mine much of their subversive power from their careful unfolding (and subsequent rugpulling) of the Pretty Woman (1990) and Elephant Man (1980) playbook.

Meanwhile, The Substance delivers the squelchy physical devolution of The Fly (1987), but its broad attempt to overlay feminist themes barely stand up to scrutiny.

However good they are - and some truly are great - these movies are strict subsets of earlier films. Their ambitions feel constrained, their identities small. This closed-loop cinema feels oddly hermetic: cinema as Narcissus, obsessed with its own reflection.

Arguably, this trend was catalysed by Quentin Tarantino, the great jukebox of cinema history. Tarantino is a freak in his ability to force his openly “stolen” influences through his own esoteric, toe-tapping tastes. But most directors aren’t Quentin Tarantino, and the obsession with speaking directly to older movies leaves their movies feeling one step removed from the Source.

There’s a difference, for example, between Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) and James Gray’s Ad Astra (2019). Though both adapt Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Ad Astra feels diluted: more indebted to Apocalypse Now than the source text.2 It reaches within the screen, rather than beyond it.

We’re seeing this trend extend into criticism. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve read/heard someone say a new movie is actually “about the filmmaking process.” Now, I'm sure there’s truth in this: I believe in auteur theory, and if directors put a bit of themselves into a movie then, naturally, that will involve them moaning about the day job. But I find this such a boring perspective! Is that really the most interesting thing to say about the film?

This is, for the record, why I am not interested in seeing another film calling itself a “love letter to cinema.” The more cinema talks to itself, the more that it becomes a niche interest for freaks like us who enjoy watching, Leo meme-style, for things we recognise. If movies are to recover their cultural relevance, they have to speak to something outside of themselves.

So, how can we break the loop?

Well, as I said in my intro, today is a day for problems, not solutions. I’ll deal with those in my next piece. But here’s a hint: not all 2024 films were of the closed-loop variety. In fact, our exit route involves leaving the Hollywood hills and heading for a rural Japanese village, where a young director sits, eyes closed, and hears a piece of music that changes everything….

These posts take time. I want to keep them free for now, but if you've enjoyed my work and would like to support it, please consider buying me a 'coffee'. I enjoy writing in coffee shops, so you would quite literally be fuelling my next piece!

I was trying to think of a resurrected Direwolves metaphor to use here, but have come up blank. If you can think of one, congrats, you’re funnier than I am.

Apocalypse Now itself was inspired partly by the hallucinatory madness of Werner Herzog’s 1972 masterpiece Aguirre, the Wrath of God, but nevertheless is able to tap into the source text in a way that Ad Astra can’t.

Your observation reminds me of Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism. Cinema’s self-reflexive nature seems to be yet another product of late-stage capitalism.

Looking forward to your potential solutions! 🌟

I get where you’re coming from. It reminds me of season 2 of White Lotus when they made all those Lavventura references. It was cool to see but felt shallow because it wasn’t attempting to say something fresh, based on its own layers.

I think there should be encouragement around the study of film theory and philosophy in filmmaking instead of just watching movies. Sure, there’s a lot to watch that is “relevant,” “necessary,” “influential” or whatever you might call it. However, such a curriculum biases a group of film students toward the mimicry and esotericism you’ve described.