Television Was Supposed to Kill Cinema. It Failed.

The weird, unpredictable ways TV changed the movies

Hello friends

MOVIES ARE DYING!

If you’re sick of reading that headline, you’re not alone. That same frustration is what led me to write today’s piece.

Seventy years ago, this same panic consumed Hollywood. With the dawn of television, movies were supposed to be dead, extinct, kaput.

Spoiler: they weren’t. Yes, they changed enormously. Not always for the better. But the impact of television was way weirder, more diffuse and more interesting than anyone predicted.

Today, streaming is supposedly finishing what television started. But if history tells us anything, it’s that we should think twice before declaring the death of cinema.

This essay is about what actually happened the last time something “killed” the movies.

I. The Battle of the Smellies

December 2, 1959. Something is brewing in the bowels of the DeMille theatre.

Cufflinks, diamonds and champagne. On screen: Behind the Great Wall, the first feature-length documentary by a Western director in China. An afterthought.

Tiger hunts and orange slices. A fisherman’s jet-black bird retrieves an unsuspecting salmon; the crowd mumbles their approval.

Then: it’s released. Seeps from the air conditioning in a fine mist, catching the projector like dust in a streetlight. Citrus… bitter… not bad. Then more. Dozens of them. Each heralded by white subtitles splayed across the screen. Each welcomed with a groan. Jasmine, soy sauce, tiger, grass, pine. They combine into one big stink; a cinematic Dutch oven.

Pinched noses; scrunched brows. Pencils already scratching. “Strong enough to give a bloodhound a headache,” declares Time.

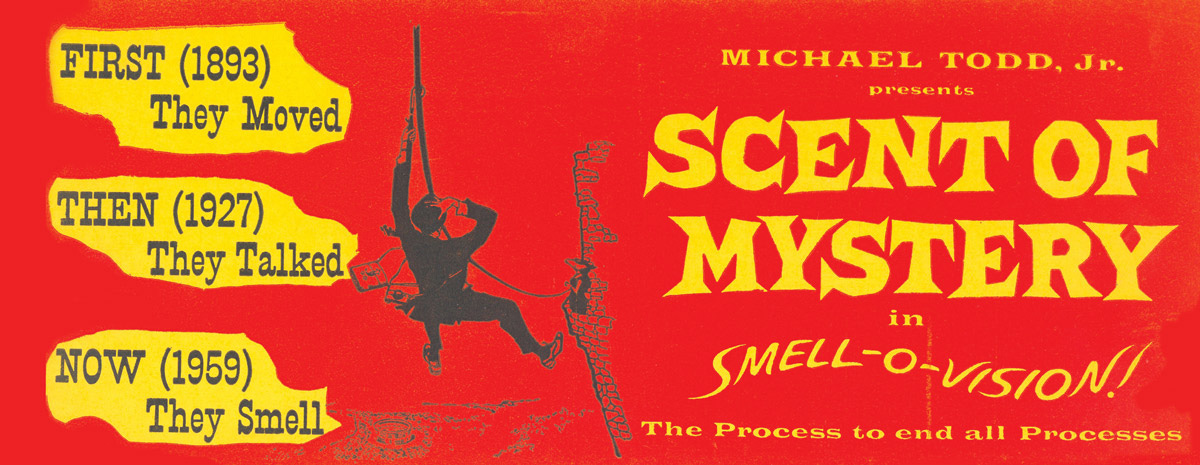

AromaRama was its name. The first “smellie” ever commercially released.

Not the last. A few weeks later, Scent of Mystery premieres, starring Casablanca veteran Peter Lorre.

AromaRama was a gimmick. Scent of Mystery uses a different technology. Smell-O-Vision is supposed to be the real deal.

Its mogul backer, Mike Todd Jr, pulls out all the stops. LP soundtrack; limited edition perfume; paperback edition; publicity stills. Elizabeth Taylor is flown out to demo the tech to eager studio executives. A defence contractor is tapped to manufacture hundreds more machines.

The film begins. One by one, thirty smells are released with a distracting hiss. A hint of brandy floats through the theatre as a character sips his coffee. Someone slips in a busy market; the scent of banana skin identifies the culprit.

Time offers a faint whiff of praise. “At least [the smells] don’t stink so loud” as the toxic fumes of AromaRama. It’s a Pyrrhic victory. The smelly winter is over. Neither technology would be commercially used again.1

II. Viva La Revolución

Something else lingered in the late 1950s Hollywood air. The smellies were just the latest desperate salvo in what was fast becoming an all-out war.

The defenders: the behemothic movie studios who had dominated American entertainment since the 1920s.

The aggressor: television.

The small screen had threatened to come for movies ever since the 1920s. War and depression had held it at bay. No longer. Television spent the 1950s mercilessly encroaching on cinema’s turf.2 The result: thousands of theatres in the red, with thousands more barely in the black.

Not since the introduction of sound had cinema faced such a threat. If any Tom, Dick or Harry could flip the box on from their couch, why would anyone pay their hard-earned money to go to the cinema?

Samuel Goldwyn (as in the “G” in “MGM”) saw the writing on the wall.3 “The thoroughgoing change which sound brought to picture making will be fully matched by the revolutionary effects […] of television upon motion pictures,” he declared in 1949. “I predict that within just a few years a great many Hollywood producers, directors, writers, and actors who are still coasting on reputations built up in the past are going to wonder what hit them.”4

By the late 1950s, the movie industry had spent nearly a decade scrambling for the silver bullet that would stop television in its tracks. The smellies were just the latest misfire. A few years previously, major studios had launched ambitious 3D projects, culminating in Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder in 1954. The movie was a triumph; the technology…less so. By 1955, the 3D experiment had been abandoned.

Goldwyn was right. Television was revolutionary. American theatre attendance never returned to its pre-war peak. The studio system collapsed, ending the careers of hundreds of establishment figures who’d grown comfortable in the ancien régime. Movies changed, perhaps irreversibly.

But reports of cinema’s death were greatly exaggerated. The smellies were a wet fart of a response. But they weren’t the only response. Movies found new ways to combat, ally with, and learn from their cocky young rival.

Far from killing the movies, television caused a shockwave of technical, formal, stylistic, production and marketing innovations that endure to this day. These were complicated, diffuse and unpredictable. Some were positive; others weren’t. But none were terminal. Cinema endured. There was life in the old dog yet.

III. Yes, Size Matters

It didn’t take long. Within a couple of years of television’s rude arrival, cigarette-chomping Hollywood executives had arrived at a consensus.

Thanks to television, routine fare no longer cut the mustard. Audiences “will no longer buy tickets at the theater, except to see the very highest form of entertainment,” declared the vice president of Paramount. “Far superior to what they can see on television free.”5

Movies needed to Go Big or Go Home. Like any suitor whose pride is under threat, Hollywood set out to expose the cocky young upstart for the fraud it was: convenient, maybe, but sorely lacking the goods in the trouser department.

3D and the smellies backfired. But these were small experiments. Meanwhile, studios were rolling out their big guns.

First, image size. By the 1940s, the industry had settled on the boxy “Academy” aspect ratio of 1.37:1.

Like an annoying little brother wearing his older sibling’s hoodie, television stole that ratio and made it its own. So, the big brother changed styles.6 Goodbye box, hello rectangle. In 1953, 20th Century Fox debuted its CinemaScope technology, whose ratio was a glorious 2.35:1:

Widescreen had arrived. Over the coming years, many studios either rented CinemaScope or explored competitors, marketed with confusingly similar names like Cinemiracle, Cinerama and VistaVision (used in two magnum opuses: Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and John Ford’s The Searchers (1956)).7

Some filmmakers despaired. “The long and narrow frame is only good for filming snakes and funerals,” deplored Fritz Lang. Close-ups had long been relied on to showcase emotion and beautiful actors. Who wouldn’t want to see every detail of Grace Kelly’s face on a 20-foot-high screen?

Now, this weapon was firing blanks. In widescreen, the conventional close-up left a distracting space on either side of the subject’s face. Even worse: early widescreen technologies were anamorphic. The edges of subjects’ faces were distorted and stretched, an effect tastefully known as “the mumps.”

Many responded by reviving an old silent era trick of “clothesline” compositions: arranging actors horizontally across the frame.

It was a pretty bland strategy. These early clothesline movies ended up looking shallow, unimaginative. “I don’t know how to direct people in a row,” complained one director. “Nobody stands in rows!”8

By the mid-1960s, these teething pains evaporated. Anamorphic lenses were toast. The non-anamorphic, less distorted Panavision (also 2.35:1) had emerged as the industry standard. Clothesline composition was sent back to the depths from whence it came. Widescreen’s victory was total. 1.85:1 or 2.35:1 ratios became the norm.

Ford’s desert; Kubrick’s space; Cameron’s sea. Thanks to television, the great vistas of cinema were born.

Image size wasn’t the only thing getting an upgrade. In 1939, The Wizard of Oz had wowed audiences by piercing Kansas’ monochrome drudgery with the glorious technicolour of Oz. But market and technological forces had conspired to keep colour movies rare in the years that followed.

That all changed in the early 1950s, when Eastman introduced a less vibrant, less detailed, but easier to process alternative to Technicolor, imaginatively named Eastmancolor. Now, more movies could show off all colours of the ‘bow and stick one up to television in the process.

While widescreen remained a competitive advantage for cinema, the small screen quickly adapted to the threat of colour. By the early 1960s, television and cinema weren’t simple enemies anymore. Even as the studios bemoaned television’s impact, they gorged themselves on the young upstart’s cash by selling their libraries for syndication. These devil’s bargains were profitable, with Warner Bros chalking up $21 million by selling its entire pre-1950 library to Associated Artists Productions in 1956.

So, when colour televisions hit the market in the 1960s, networks weren’t interested in dusty old black and white movies. They wanted the real deal: full-throated colour bonanzas. Studios became even more incentivised to shoot in colour, to preserve that sweet, sweet resale value. What had started as a middle finger to television quickly became a way to keep it on side.

Confronted by the tube, movies got wider. They got more colourful. They even got louder, with more theatres introducing stereophonic sound.

Television was small. Poxy. Pathetic. Now, movies became the opposite. Studios wanted to show off their shiny new toys. Dramas and intimate romances were out. Big-budget epics and musicals were in.

Through the 1950s and early 1960s, studios released fewer, more expensive films, like Cecil B DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), which was shot in VistaVision with colour by Technicolor. Billed as “the greatest event in motion picture history,” it made $122 million off a $13 million budget.

Increasingly, movies were a hits business. That delicious, warm, oozy middle of medium-budget programmers - the type of fare that thrived in the Good Old Days - was being spooned out. Blockbusters became the defining studio product.

The middle was up for grabs.

IV. Boobs to the Rescue

American cinema had been in crisis before. Back in the 1930s, the Great Depression had taken a sledgehammer to the industry, forcing it to take desperate measures to stay afloat.

Cue: the double bill. Patrons were now treated to three hours of entertainment: the main feature, an 80-minute ‘B’ feature, plus bells and whistles like news reports, cartoons and trailers. A smart solution. Attendees got more bang for their buck and theatres, thanks to regular intermissions, earned a tidy sum from all the greasy paws at the popcorn stand.

The success of this model caused an explosion in demand for ‘B’ movies to package alongside the main feature. The studios responded by setting up specialised units to churn out cheaper, less prestigious fare with lesser-known actors and shonkier production values.9

By the mid-1950s, this model was on its knees. Since television had strutted onto the scene, and Go Big or Go Home had taken effect, cheap and cheerful B-movies weren’t cool anymore. Even worse: a 1948 antitrust ruling prohibited studios from block booking and owning theatres, robbing them of a guaranteed way to ship this product.10

The appeal of low-budget production disintegrated. Thousands of rural and suburban theatres were left in the lurch. With fewer movies being made, and big-budget films spending longer playing first-run engagements in large urban cinemas, they were thirsty for product that the studios were no longer providing.

Which meant… **OPPORTUNITY**

Television forced studios to cede the low-budget field. Several independent companies and filmmakers emerged to fill the gap. Some were unsuccessful, like Ed Wood, whose attempt to dive into these newly open waters was a critical and commercial bellyflop.

Others were triumphant. None more so than the King of the Bs himself: Roger Corman, who spent his long career churning out low-budget, profitable films.

Recycled sets; cheap rubber suits; a skeletal crew: Corman used every trick in the book to cut costs. For Monster from the Ocean Floor (1954) he operated as producer, grip, driver and director, making $185k from a $12k budget.11

His films weren’t good, but they were quick, cheap and made money: in 1956 and 1957 alone he directed or produced twelve (yes, twelve) movies, all of which turned a profit.

Corman’s partner in crime: American International Pictures (AIP). Founded in 1954, AIP was one of the great success stories of postwar American cinema, grinding out product at an astonishing rate.

Television primed the market for AIP’s emergence. Drive-in theatres exploded from a few hundred in 1947 to over 4,000 by 1957, their carnivalesque atmosphere a welcome diversion from the living-room drudgery of the small screen.12 They proved eager buyers for the high-concept, low-execution and unapologetically titillating style that was fast becoming AIP’s bread and butter.

The new studio’s powerbrokers had realised something. Watching television with the parents was agony for America’s newly empowered youth. While the oldies decayed on the couch, AIP put all its energies into producing movies designed to entice “the gum-chewing, hamburger munching adolescent.”13 Their method: cash in on the lurid material never shown on television: breasts, booze, drugs and blood.

William Castle was never that interested in breasts, booze or drugs, but he more than made up for it in blood. In 1958, he released Macabre, a vanilla horror film sold on a genius gimmick: Lloyd’s of London insured anyone who saw it for $1,000 against death by fright. It was a triumph. Macabre made $5m on a $100k budget.

A string of marketing coups followed. Electric shocks delivered to the audience (The Tingler, 1959). A glow-in-the-dark skeleton plunging from the ceiling (House on Haunted Hill, 1959). A Fright Break where cowards could claim a refund if they were too scared (Homicidal, 1961). One man’s flair for the dramatic achieved what the smellies couldn’t: lured audiences away from their televisions by eventising the movies.

As indies parked their tanks on the studios’ lawns, foreign countries began to take note.

During Hollywood’s golden era, countries around the globe had been mainlining American product. Now, thanks to Go Big or Go Home, there was less of it.

National cinemas emerged worldwide. In the 1950s, Burma, Pakistan, South Korea and the Philippines produced more films annually than most European countries. Egyptian films blossomed. Hong Kong produced 250 feature films in 1962, more than the US & Britain combined. The French and Italians developed film festivals and export sales organisations to ship their product overseas. By weakening the American movie business, television had exploded cinema as a global artform.14

A reminder of the story so far. Movies go big to fight television. They leave a gap in low-budget production. A new wave of indie filmmakers and companies gladly step in.

But were many of the resulting movies any good? Well… not particularly. 15 There were some highlights, including Roger Corman’s critically acclaimed run of Edgar Allen Poe adaptations. But there was a lot of shlock. Horny 19-year-olds tend to have different aesthetic standards.

Still, who said boobs and monsters can’t be influential. The preoccupations of the 1950s and 1960s indie wave: monsters, space, action and sex, percolated into the mainstream, even as the more salacious edges were sanded off.

By the 1980s, high concept, genre-oriented spectacle had become synonymous with “blockbuster.” “What was Jaws,” asked one executive, “but an old Corman monster-from-the-deep flick—plus about $ 12 million more for production and advertising?”16

Beyond genre, the modern blockbuster model Jaws kickstarted in 1975 was built on the marketing and distribution methods that AIP and others had spent years refining. These included opening in many theatres at once, targeting specialised audiences (backed by ruthless audience testing), a concept-rather-than-script-first development process, summer releases, and relentless television advertising.

Modern Hollywood borrowed more than monsters and marketing from the 1960s independents. Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Jack Fisk, James Cameron, Joe Dante, Jonathan Demme, Sylvester Stallone, Gale Anne Hurd, Bill Paxton, Ron Howard, Peter Bogdonavich, John Sayles, Robert De Niro, Peter Fonda, and dozens others got their starts under Roger Corman, churning out the low-budget, low-risk product that television had opened the market for.

But Corman wasn’t the only talent farm in town…

V. Hatching the Golden Geese

“Remember, men, we are not doing GONE WITH THE WIND!”

So began George Justin’s message to the cast and crew.

“We are doing a very fine, sensitive, beautiful, highly dramatic, VERY LOW BUDGET picture. Let’s get in there and knock off lots of scenes today.”17

It was 1956, and the film was 12 Angry Men. Justin, the production supervisor, had been tasked with keeping the shoestring production on track and under budget.

From conception to talent to execution, the movie would not have happened if it weren’t for television. The story first debuted as a live production on CBS. Now, it was moving to the big leagues. Behind the camera: Sidney Lumet, only 32, who had also cut his teeth on the small screen, rattling off ten rehearsals and two live performances per week for the two shows under his command (You Are There and Danger).

To 12 Angry Men, Lumet brought the no-nonsense production methods he’d sharpened in television: relentless rehearsals, detailed shot diagrams, hand-drawn blueprints and alphabetical setup guides. He completed the film on schedule and under budget.

Discipline. Lumet had it in abundance. But he borrowed more than good planning from the tube. 12 Angry Men’s aesthetic - naturalistic, character-driven, confined and dialogue-heavy – was forged in the relentless production cycles of television.

A wave of small-scale, character-driven dramas shaped by television washed across American screens in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with directors like Delbert Mann (Middle of the Night, 1959), Arthur Penn (The Miracle Worker, 1962), John Frankenheimer (Birdman of Alcatraz, 1962 ) and Martin Ritt (Edge of the City, 1957) getting their starts on the small screen.18

The naturalism of television bled into acting styles, too. While the mumbling intensity of the Method had its roots in Stanislavski and Strasberg, it was through intimate, live anthology series like Studio One and Playhouse 90 that it entered the American mainstream, offering opportunities for actors like Paul Newman and James Dean to flex their emotional authenticity.

Television was the incubator for all kinds of golden geese. Hundreds of film actors, directors and below-the-line craftsmen were hatched in the warm comfort of the small screen.

Few professions benefited more than cinematography. In the old days, becoming a cameraman was a painfully incremental process of apprenticeships and obedient adherence to studio hierarchies. Now, thanks to television, the old hierarchies collapsed as demand for new talent skyrocketed.

Néstor Almendros (Days of Heaven, Kramer vs. Kramer) churned out newsreels in Cuba and school television in France. Bill Butler (The Conversation, Jaws) helped construct one of the first commercial TV stations (WGN, Chicago). Billy Fraker (Bullitt, Looking for Mr. Goodbar) worked as a loader on the Lone Ranger. Billy Williams (Sunday Bloody Sunday, Gandhi) got his start in commercials. A generation of hungry, inventive young cinematographers was born.19

This young, iconoclastic new wave of talent brought a new set of tricks to the party…

VI. Direct and Dirty

Ah, the Good Old Days.

Once, visual nonfiction had been subject to the whims of the studios, the government, and other large organisations who could afford to wield a camera. Video news was confined to short newsreels planted between theatrical double bills. And the long-form documentary was largely a Morally Appropriate™ informational tool, with confrontational fare never really finding a home on the big screen.

Then came television. Thanks to TV news, cinemas lost interest in newsreels. And the small screen proved a new market for intrepid long-form documentaries. As lightweight, portable 16mm cameras and sync-sound recording emerged, cinema could take to the streets like never before.

The result: Direct Cinema (and its French cousin, the sexier-sounding cinema verité).20 A new visual language emerged: street-level, subjective, and gritty.

In documentaries, this unlocked new perspectives. Narratives could now be retrofitted from hundreds of hours of fly-on-the-wall footage, from the gritty urban reality of Shirley Clarke (The Cool World (1963)), to the behind-the-curtain portrayals of Bob Dylan (Don’t Look Back (1967), D.A Pennebaker) and the Rolling Stones (Gimme Shelter (1970), Maysles Brothers).

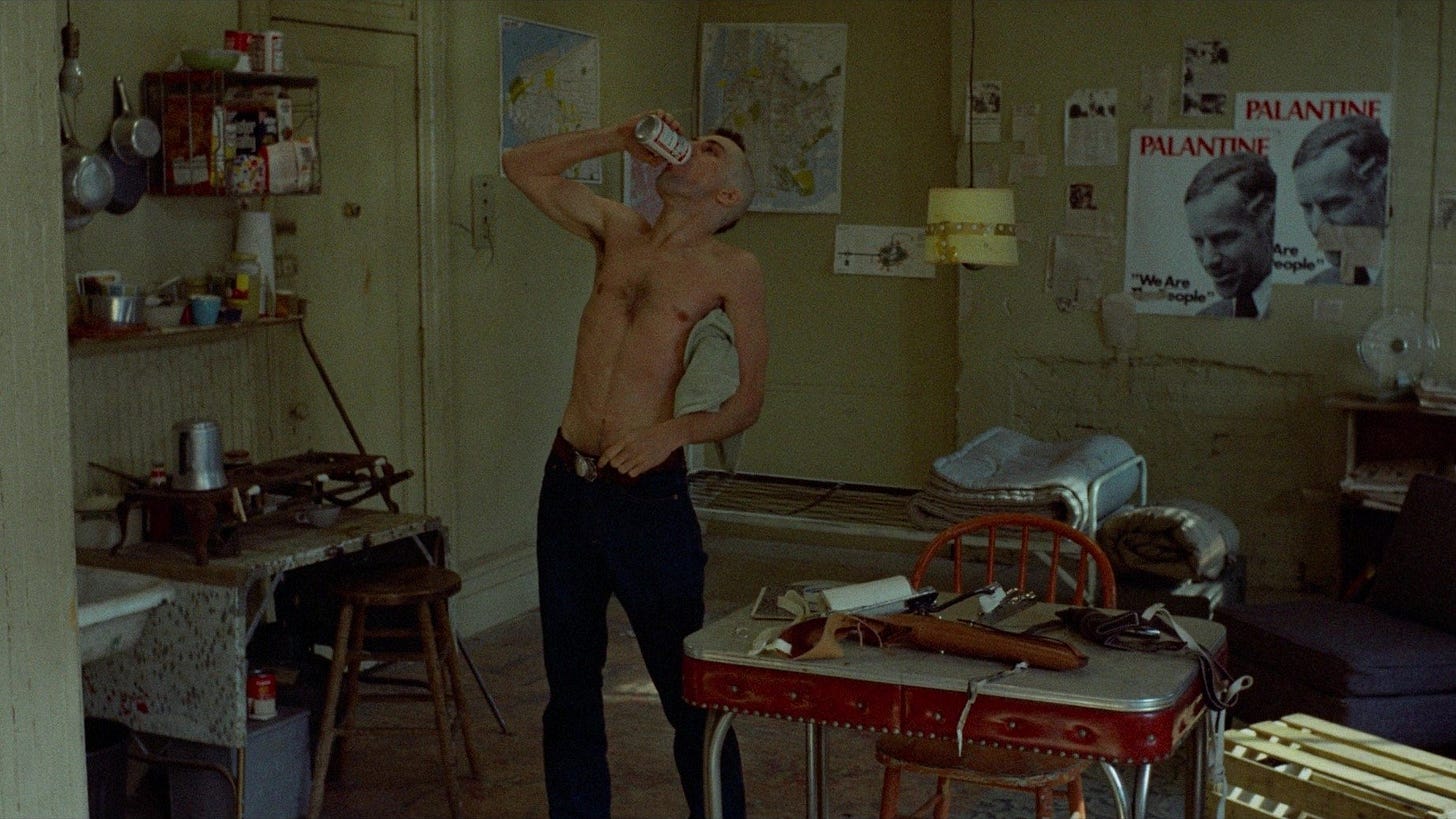

But the new aesthetic bled into fiction, too. Street-level perspectives emerged, as filmmakers like John Cassavetes, Arthur Penn and cinematographer Haskell Wexler pierced the romanticism of classical Hollywood with a dirtier documentary aesthetic.

By the late 1960s, the timebombs that television had planted under Hollywood were ready to explode. A wave of young, independent talent, armed with gritty, urban aesthetics and a freshly grounded acting style could target newly empowered youth audiences while the slow-moving and crumbling studio system was left gasping in the wreckage.

When The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967) captured audiences across the country, the New Hollywood was born.

In the 1970s, a new canon of American cinema emerged, including The Godfather, Taxi Driver, Apocalypse Now, Dog Day Afternoon, Raging Bull, Badlands, Chinatown, The French Connection and dozens more.21

This was the funhouse mirror inversion of Go Big or Go Home. In the 1950s, studios had responded to television by emphasising scale and moral clarity. Now, the proponents of New Hollywood did the opposite, substituting scale (with some exceptions) for style, sex and moral sophistication.

Gritty realism wasn’t the only way that New Hollywood cinematographers stood out from the small screen.

Zoom lenses were nothing new, but the arrival of televised sports had popularised them. Filmmakers took note. Over the pond, Claude LeLouch’s A Man and a Woman (1966) used long telephoto lenses with wide apertures for a painterly effect.22 Objects outside of focus became beautifully blurry blobs (later known as “bokeh,” which sounds vaguely inappropriate), an effect that television cameras could rarely achieve.

Now, New Hollywood directors and cinematographers like Robert Altman, Vilmos Zsigmond and László Kovács borrowed this aesthetic for films like McCabe and Mrs Miller, The Deer Hunter and Shampoo.

By the end of the 1970s, the New Hollywood was dead. The Jaws blockbuster model, its roots in the AIP independent scene of the 1950s and 1960s had taken hold.

What had once been a vicious rivalry between television and cinema had long since evolved into an uneasy alliance. With the emergence of VHS in the 1980s, it would blossom into a full on co-dependency.

VII. Movies Bend the Knee

Cash; dollar; skrilla; dough. Television, and the VHS market it enabled, became far too lucrative for the movie industry to resist.

Filmmakers (and the studios breathing down their necks) began to bend the knee. Conscious that their output was going to be consumed on television, they chose to “shoot and protect” their movies: confining key areas of action to a safe area within the frame.23

While these films were shot in widescreen, they sacrificed the format’s potential for safer, more limited compositions that wouldn’t be ruined on the small screen. Singles and over-the-shoulder shots became more popular.

Meanwhile, the concerns of Goldwyn - how could movies keep people interested in an age of television - had never really left. With 1,000 other distractions at home, filmmakers needed to find ways to distract viewers from hanging up the washing or feeding the cat.

The easiest solution was to cut more. More cutting = more stuff happening for our greedy little eyes. Yum yum yum. Average shot lengths plummeted.

While shot lengths plummeted, close-ups were back with a vengeance.

Early concerns about empty space were long gone. Thanks to Sergio Leone and the 1960s, the polarity between extreme facial close-ups and wide shots entered cinematic vernacular.

But the aesthetic appeal of the close-up had a more practical purpose. Close-ups were way easier to parse on smaller screens. “It’s a shame that most films rely so much on tight close-ups all the time,” said one cinematographer in 1995. “The style is really just a result of what producers want for video release.”24

The style that David Bordwell calls “intensified continuity” emerged, defined by fast-cutting, close-ups, a moving camera and polarised lens lengths.

Cinema had once responded to television by becoming more cinematic. Now, it was becoming more televisual.

VIII. The Revolution Was Televised

By the 2000s, the battle of the smellies was ancient history.

Films had become more televisual. Serialised storytelling, pop soundtracks zooming cameras, rapid-cutting, soft focus and complex multipart ensemble narratives were as common on the big screen as they were on MTV.

Meanwhile, television was increasingly cinematic, boasting higher production values, A-grade talent and the type of moral complexity once reserved for the cinema. It had even gone widescreen!

The downsides of modern cinema are well documented. The art of blocking – actors moving in and out the frame, in depth – feels all but lost. After a brief revival in the 1990s, the mature intelligent blockbuster model has been replaced by Corman on steroids. Theatre attendances continue to plummet.

The story isn’t over. The old enemies are once again taking to the battlefield. Once again, reports of cinema’s death are abundant. Television is a greedy little fucker. The uneasy alliance it reached with cinema wasn’t enough. In the last five years it has gone for the jugular. Streaming.

Reports that Netflix will be purchasing Warner Bros. have triggered a fresh wave of handwringing. With box office revenues crumbling and studios consolidating, the It’s So Over crowd is in the ascendance. It’s 1949 all over again.

But if we’ve learned one thing from the last 70 years (and several thousand words), it’s that the effects of streaming are likely to be far more diffuse, unpredictable and diverse than we realise. Television gave us the New Hollywood, direct cinema, independent film, the high-concept blockbuster, the burgeoning of world cinema, widescreen, colour cinematography and a talent-tsunami.

Few who feared that television would kill movies could have predicted these long-term effects; fewer still would try to claim that cinema would be better off without them.

Back in 1949, Samuel Goldwyn had warned that television would lead to a revolution. He was right. Perhaps that’s a good thing.

If you’ve enjoyed my work and would like to support it, please consider subscribing or buying me a ‘coffee.’ If you haven’t enjoyed it, what are you still doing here! Go outside!

For more on the battle of the smellies, check out chapter 8 of What the Nose Knows: The Science of Scent in Everyday Life; by Avery Gilbert.

The Battle for the Bs: 1950s Hollywood and the Rebirth of Low-Budget Cinema by Blair Davis covers this in depth. There were 82 million cinema admissions in 1946. Nearly 20 percent of Americans’ entertainment money was spent on movie tickets. By 1955, there were fewer than 46 million admissions (despite the US population rising by 26 million), with only 7 percent of entertainment spending attributable to movies.

Samuel Goldwyn had already sold his shares by the time Goldwyn Pictures Corporation was merged into MGM in 1924. He unsuccessfully sued to have his name removed from the new company.

The Battle for the Bs; by Blair Davis.

The Battle for the Bs; by Blair Davis.

Boxes are back, baby. Filmmakers like Lynne Ramsay, Robert Eggers and Wes Anderson have embraced the old square Academy ratio to… you guessed it, differentiate their movies from the now ubiquitous widescreen.

VistaVision has made a surprise comeback, with The Brutalist (2024), One Battle After Another (2025) and Bugonia (2025) all using the technology, in part to set the films apart from the digital sheen of streaming.

David Bordwell, as always, is the king of this stuff. This quote, and the broader arguments about the impact of widescreen technology, are covered in Chapter 10 of his Poetics of Cinema.

Many specialist companies were also established to produce low-budget films, including Monogram, Republic, and the dime-store studios known as Poverty Row. Many of these went out of business with the collapse of the studio model.

The significance of this ruling can’t be overstated. Whereas studios had previously been vertically integrated (able to handle all elements of production and distribution in-house), now they were broken up, replaced by a package system under which each film could be made and released by a magpie’s nest of different support firms. The implications of this are outside the scope of this piece, but they were big!

Both the budget and the box office are debated (see here for more). Regardless of the final figures, it’s clear that the film turned a tidy profit.

Two books are particularly helpful on AIP, Corman and the indie revolution: Celluloid Mavericks: A History of American Independent Film Making; by Greg Merritt and The Battle for the Bs; by Blair Davis.

Film History: An Introduction; by Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell.

Film History: An Introduction; by Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell.

Around the same time, a much smaller but more artistically interesting underground wave was emerging, populated by filmmakers such as John Cassavetes.

Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers; by Beverly Gray.

For more on the production of 12 Angry Men, check out Reginald Rose and the Journey of 12 Angry Men; by Phil Rosenzweig.

These directors would subsequently diverge in significant ways. The expansive dynamism of Frankenheimer, for example, was decidedly less related to television than the chamber dramas of Ritt.

Dennis Schaefer and Larry Salvato’s Masters of Light: Conversations with Contemporary Cinematographers covers this in depth. “If it were not for the advent of television and commercials,” says the introduction, “an entire generation of intelligent and innovative cinematographers would not have had the opportunity to enter the industry and thus would not now be working in feature films.”

I expect this statement has made a film scholar somewhere very angry. Direct Cinema and cinema verité differed in some important ways. Life’s too short to explain them here.

Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls is the canonical (if controversial) account of this era. I wrote about it here.

The Story of Film; by Mark Cousins

David Bordwell is the authority on intensified continuity, and identifies the trends discussed here in his The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. I wrote about it here.

The Way Hollywood Tells It; by David Bordwell.

He's fucking back

RIP Robert Duvall.

Another Lion gone.