Keep It Simple, Stupid

How straightforward stories unlock complex cinema

Welcome to the 83 subscribers who joined us after my last post, which attempted to ward off the approaching behemoth of 'cinematic' TV. Today we dig into a paradox of cinema: as movies become more technically complex, why do the stories themselves remain stubbornly familiar…? In the process, we welcome a new guru to the Rough Cuts canon...

One of the coolest things about cinema is that, relative to our other great arts, it is so new.

Literature and theatre have been around for a few thousand years. Art and sculpture for tens of thousands. Cinema? Barely 120!

We’re speedrunning the evolution of a new art form. Cinema has gone from the cradle to maturity faster than its elders took to learn their first words.

“The development of language from Griffith to Godard in films is roughly equivalent to that from Chaucer to Joyce in English literature,” wrote legendary director Satyajit Ray in 1971.1 “A matter of 600 years as against 60 in the cinema.”

The reference to Godard is no accident. Ray identifies the films of the French master as a watershed moment in cinema’s development, a Rosetta Stone for the “terse, muscular, elliptic” style that followed. The post-Godard emerging cinema of 1971 was, in Ray’s words, “marked by a greater density than the old one. More is said in less space and less time.”

Another 50 years have since passed. Godard’s innovations — handheld cameras, shaggy dialogue, jump cuts, and fractured chronology — have been compounded by countless more, revolutionising how we tell stories on the screen.

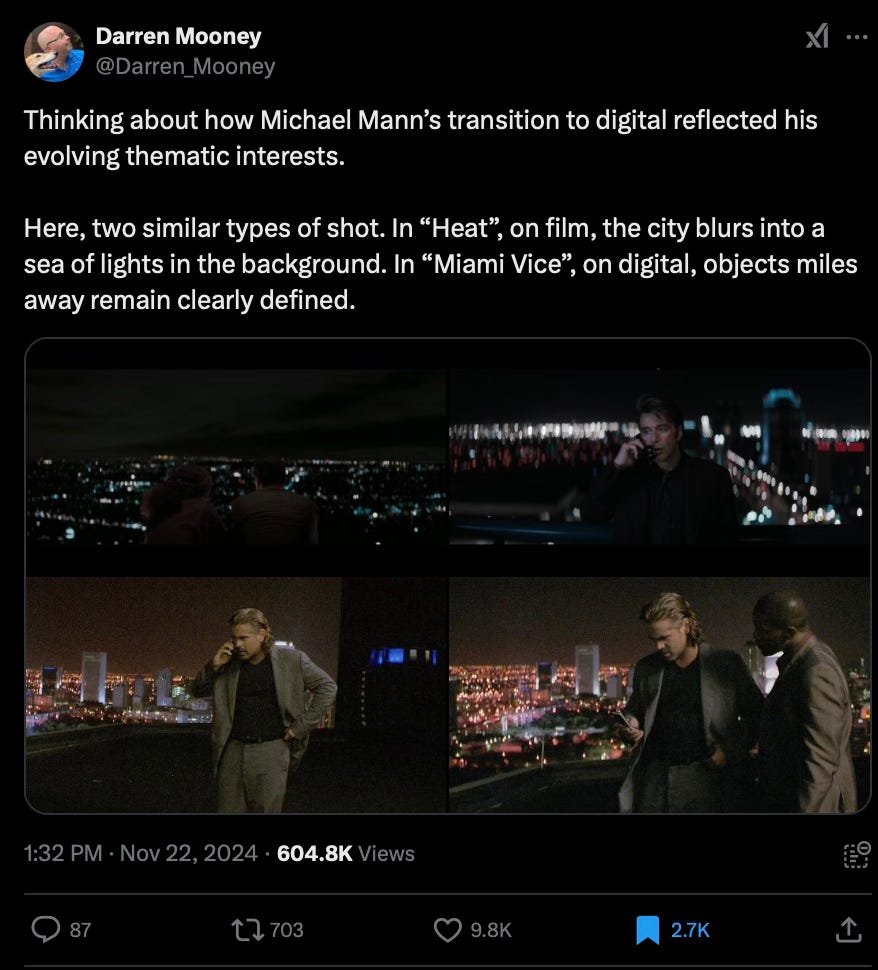

Take the advent of digital photography in the late 1990s, enabling filmmakers to cram way more information into the frame:

Or the introduction of the Steadicam in the mid-1970s, whose smooth fluidity emulates human perception more naturally than the shakiness of handheld cameras:

Or the rise of non-linear, puzzle-box narratives in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, where fractured, multilayered plots are sliced up and shuffled together:

Today, cinematic language is terser, more muscular, and more elliptical than ever. We have partially black-and-white $1 billion blockbusters told non-chronologically over three intercutting timelines. We have feature-length films directed from a first-person (or first-ghost) perspective. We have vastly immersive worlds recreated through 3D imagery, underwater cameras, and microscopically detailed technical effects.

Cinema now speaks in many tongues. But even as its vocabulary expands, what it is actually saying has remained stubbornly persistent. Stories on the screen feel distinctly familiar.

Whether it’s literal retellings of the same narratives (Nosferatu anyone?), familiar frameworks like the Hero’s Journey, or reliable genre beats that our grandparents would recognise, archetypal storytelling is alive and well. Even big art house swings like this year’s The Brutalist fit within a prepackaged lineage of The Godfather-style American epics.

Ray noticed this, too. “The convention of narrative in whatever shape or form has remained,” he argued. “By discarding the story altogether one would be destroying the very basis of a film that a lot of people are expected to see and like.”

Now, I am doing everything in my power to resist turning this into one of those boring guides about how there are only seven story archetypes or how all stories are ultimately the same, blah blah blah. To be honest, I’ve always found that take dull and reductive. I’m more interested in why. Why do even the most ambitious movies feel so instinctively familiar? What does this tell us about cinema as a medium?

Enter Ray. He suggests that straightforward story frameworks unlock, rather than preclude, a movie’s complexity.

To understand why, consider this (forehead-slappingly obvious) truth. Even as its vocabulary has expanded, cinema remains bound by the same fundamental constraint that Buster Keaton, Fritz Lang, and Georges Méliès grappled with a century ago.

Time.

“A film-goer’s time is not his own time,” says Ray. “Everything in the cinema […] unreels at the constant speed of twenty-four frames per second. One cannot shut the film and think.”

Watching a movie is an act of submission. Unlike books, which unfold at the reader’s pace, films unfurl at the filmmaker’s clock.2

Ray offers Joyce’s Ulysses as an example:

Wolf this down, and it will barely register. Pause and savour every word, and it will melt in the mouth. Cinema offers no such luxury. Movies are not designed to be lingered over sentence by sentence, frame by frame. No matter how much information is packed into each shot, we have exactly the same amount of time to process it.

Movies, therefore, need to hit us on an instinctive level. There must be some gristle on the bone, something tangible we can sink our teeth into to prevent a film from slipping tastelessly down the gullet.

This is where archetypes come in. “A filmmaker who wishes to use the modern idiom has even greater need of a simple framework,” Ray says. He means that our recognition of certain archetypes primes us to instinctively connect with what the movie is doing on top of them. They are like scaffolds upon which filmmakers can innovate with structure, technique and emotional density while keeping the audience engaged.

The fact that we can’t pause and mull things over means that simple story frameworks are a feature, not a bug, of movies, particularly those that use the complex language enabled by modern technology.

Think about some of the more technically complex popular films of the last 20 years. Nearly all of them follow very simple story structures. Mad Max: Fury Road is a straightforward chase story. Avatar and The Matrix are almost slavishly adherent to the Hero’s Journey. Inception is a heist story. Oppenheimer is the myth of Prometheus. You get the picture.

Honestly, I feel like I’m just scratching the surface of this. I’ve got more questions than answers. But Ray’s ideas about simplicity in the cinema have got that little brain of mine whirring. Hopefully, yours is now whirring too!

If you enjoyed reading and would like to support my work, please consider buying me a ‘coffee…’

If you didn’t enjoy it - what are you still doing here!

There’s a whole other essay to be written on how streaming could affect this. But not today!

Hmm, have you read Sculpting in Time by Tarkovsky? He sort of posits a theory that films that follow a simple, let’s say, hero’s journey structure, aren’t actually using the DNA of cinema effectively. In many parts of the book he persuasively argues for a poetic form of cinema, something more in the mode of this year’s Nickel Boys than a film like Mad Max or The Brutalist. Personally I don’t think cinema advances are in the technical space, the look or size of lens or camera, though that stuff is definitely cool. Mad Max was special not because of any of that, but because of the way it played jazz with the form. Godard didn’t need any fancy film cameras to make his advances, in the same way that Joyce hardly needed a gelatin pen. The furthering of cinema, to my eye, is gonna come from directors who fundamentally engrain themselves into the language of cinema, who understand how to use its unique aesthetic parameters to push the art form forward. What makes it a great art form like theater or literature is that its possibilities are limitless. But it’s not the same as those art forms, and Tarkovsky argues this point all over his book, basically saying how the art form is being held back by trying to adapt to the literary form of storytelling. That doesn’t mean ‘simple’ stories are in anyway wrong, I think you’re mining something interesting here, but there does seem to be an over reliance on literary-style storytelling as a means to communicate in cinema because that’s what we, as audiences, have been adapted to accept.

This has, as you hope in the last line, got my brain whirring at top speed!

Something of a digression that your essay started for me:

I've been having some great conversations about the use of AI in The Brutalist and in Emelia Pérez, and it's been somewhat useful to compare it to previous advances in cinematic technology, the most oft-cited in these conversations being the steadicam.

So it was really interesting to read your quotation from Nathalie Morris, saying the steadicam “pushed forward the expressive possibilities of the camera”. I have to wonder whether this AI tech to "improve" the accents of actors will yield any such flourishing of the expressive possibilities of cinema? Will it expand cinema's vocabulary?