January at the Movies

Some rough cuts on Letterboxd, de Palma, mumblecore & more

“If a film is watched but not logged on Letterboxd, has it been seen at all?”

— Ancient Proverb (source unknown)

One thing I’ve noticed while idly scrolling the movie tracking/sharing app Letterboxd is that it contradicts the “keep posting and they will come” model of online audience-building.

If someone had a standalone film blog with thousands of posts, I’d expect them to have built some form of meaningful audience. Yet, on Letterboxd, I regularly stumble across accounts that have written hundreds, sometimes thousands, of reviews but ‘only’ have a few hundred followers or fewer.

And it’s not always the snappy, pithy one-liners that Letterboxd is known for. Many accounts offer insightful commentary, yet often it feels like they're shouting into the void.

My best guess is that this is because there is something intrinsically impermanent about the app. It’s easy to fire off some half-baked thoughts in a way that would feel somehow dirty on a dedicated website. Even the more measured commentary on there is usually sorely in need of editing (I re-read some of my reviews from when I first got the app during COVID, and oh boy there are some stinkers in there).

Even when edited, the longer, thoughtful commentary has no stickiness. Letterboxd’s UI, which shows you loads of reviews at a time, encourages Shiny New Object syndrome; there is always another, shorter, funnier review just a little twitch of your fingers away. If you were reading this on Letterboxd, you probably wouldn’t have got this far.

Add to this the fact that it’s a pretty self-contained ecosystem (most people just drop reviews in Letterboxd rather than sharing them more widely), and you begin to understand why putting your reps in on there doesn’t feel the same as doing it elsewhere. If you want to meaningfully engage with movies and build an audience doing so, it seems like Substack is the best place to be.

With that said, here’s what I’ve been watching this January…

Ferrari (2023; dir Michael Mann)

Sensibly steering clear of the cradle-to-grave mythologising of traditional biopics, Ferrari instead zeroes in on an intense three-month period in which Enzo Ferrari’s personal and professional chickens all come home to roost.

Mann is known for his portrayals of emotionally stunted men shielded by obsessive, myopic professionalism. Ferrari has that in spades but is more interesting for its exploration of grief as both an accelerator and a break in the lives of those it touches. Dramatic though the racing scenes are, the film really kicks into gear when it gives Adam Driver’s Enzo and Penelope Cruz’s Laura the space to silently reckon with what they’ve lost.

Frances Ha (2012; dir Noah Baumbach)

‘Mumblecore’ as a sub-genre has faced dismissal from those associated with it and derision from those averse to its bougie millennialism. As a rough approximation of a certain vibe, I still think it’s a helpful term. Frances Ha, with its naturalistic dialogue, tangential, vignette-style plot and unguarded, naive earnestness, stands out as a refreshing take on traditionally over-engineered coming-of-age narratives.

BlackBerry (2023; dir Matt Johnson)

SO FUN. I wrote about it here:

North by Northwest (1959; dir Alfred Hitchcock)

While Indiana Jones is sometimes credited with kicking off the fast-paced, theme-park-ride sensibilities of modern blockbusters, North by Northwest was pioneering this approach a full 22 years earlier.

Hailed by Guillermo Del Toro as a “perpetual-motion thriller machine,” the film also, with its globetrotting plot, tongue-in-cheek tone, and Cary Grant’s disarmingly charming lead performance, sets an urtext for the James Bond franchise and its many imitators.

Yes, it feels a little dated today, but it still packs enough punch to qualify as more than just a cultural artefact. The crop duster scene remains masterful, and the film is peppered with “did he just do that” Hitchcockian flourishes like this glorious top-down shot from the UN building 👇👇

Godland (2022; dir Hlynur Pálmason)

Last year, I watched Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God and was struck by its combination of documentary-style filmmaking with hauntingly ethereal dialogue, imagery and music.

At times, Godland elicited a similar reaction.

The film chronicles a Danish priest’s odyssey through the stark Icelandic wilderness to a village where he intends to build a church.

Unlike Aguirre, which purports to maintain a semi-objective camera perspective until later in the film, Godland’s camera is a living, breathing participant in the story, acting both as a reflection of the priest’s awe and terror and the embodiment of Iceland's elemental spirit. Filmed in a boxy 4:3 ratio, the film plunges us into this vast, disorientating and paradoxically unnatural landscape via panoramic shots and striking centre-framed images. Some of these sequences are genuinely jaw-dropping, including an extended slow pan down the rampaging torrents of a waterfall and a twisting 360-degree pan that effectively turns the movie on its head.

The first hour, documenting the priest’s journey, is the best thing I’ve seen this year. Upon his arrival at the village, Godland loses its otherworldly edge and becomes a bit too cute with its plotting and ideas. Still, all in all, this is a really exciting piece of cinema.

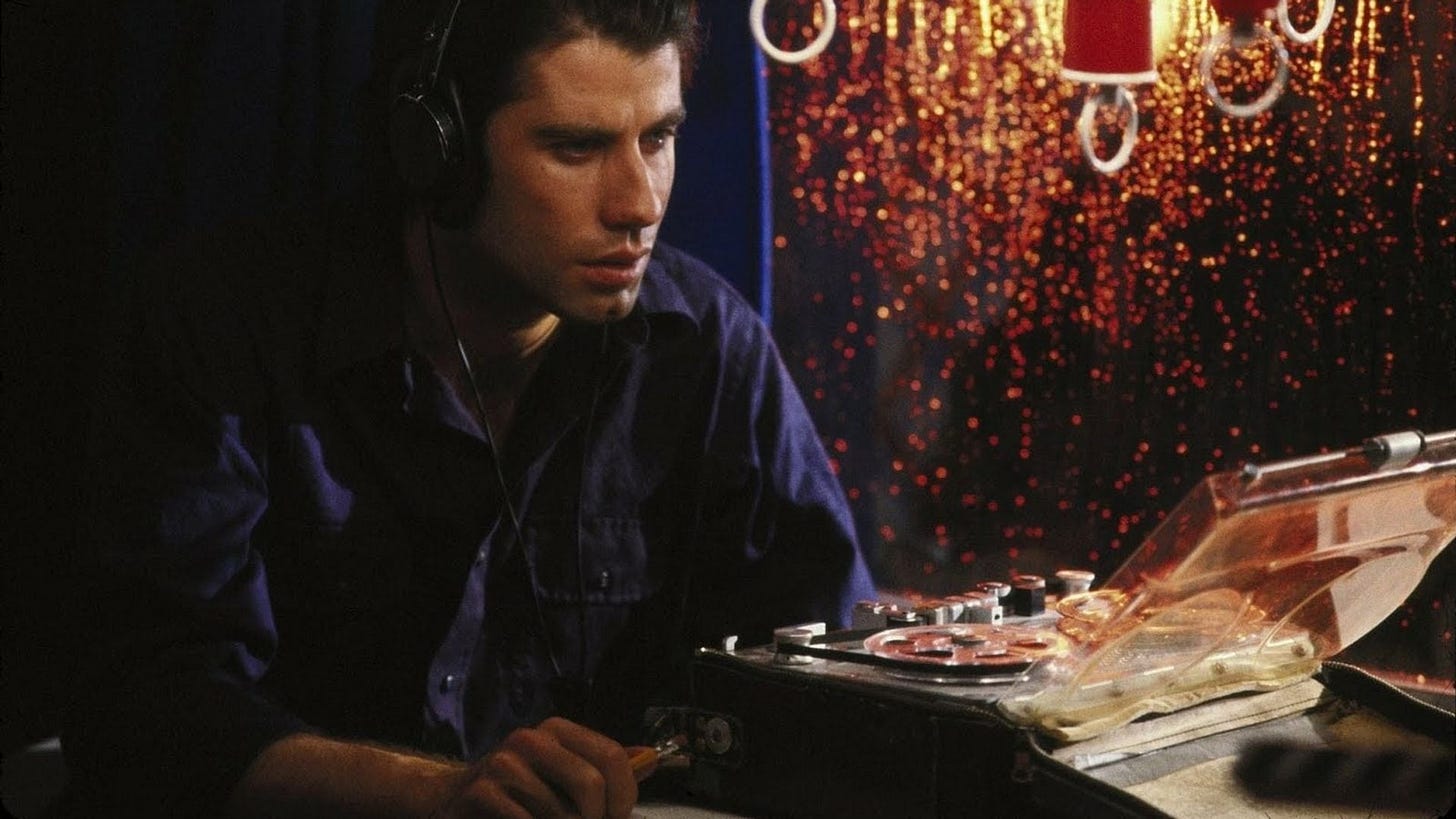

Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), Body Double (1984); dir Brian de Palma)

For reasons unknown, I felt compelled to watch Brian de Palma’s legendary run of early ‘80s thrillers last week, all riffs on Hitchcock but filtered through de Palma’s fetishistic, voyeuristic lens.

Dressed to Kill is the most conventional of the trio and also the least interesting. It ultimately rides on the twist, which makes the whole thing feel a tad underwhelming if you see it coming (it’s hard not to). Still, it possesses the surrealistic flourishes and perverted intensity that are de Palma's hallmarks, including a bravura, wordless cat & mouse sequence in a museum. That this scene is ultimately tangential to the plot adds a darkly comic layer of meta-irony.

Blow Out is the best of the three. It’s a conspiratorial thriller in the Pakula mode, a meditation on surveillance echoing Coppola, and a subversive suspense ride à la Hitchcock. Yet, such is the strength of de Palma’s aesthetic that the film ends up feeling, to this day, utterly unique. Featuring more split diopters than you can shake a stick at and one of the most memorable endings in mainstream American cinema, Blow Out subverts expectations more than any other films on this list.

Body Double is the most surrealistic. It has a plot, but it’s laughably threadbare. A Dressed to Kill style chase sequence in a shopping mall is yet more evidence of de Palma’s genius in crafting set pieces and utilising space, as is a wild sequence set to Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Relax. True to de Palma’s style, it’s darkly funny if you’re on its wavelength: the main theme, played during some of the film’s darkest moments, is an uplifting track with woozy vocals that could just as easily be deployed in a family blockbuster.

Poor Things (2023; dir Yorgos Lanthimos)

I struggled with The Lobster (the Lanthimos film I watched most recently), finding its monotonal, emotionless dialogue style and muted colour palettes abstractly interesting but little more.1 Poor Things, then, which is being sold as a feminist Frankenstein, is something of a revolution; the movie pops with heart and colour and benefits from a laugh-out-loud script. Emma Stone is as good as everyone says she is, in a role that could have easily been a disaster.

Entertaining though it is, it’s ultimately a film that suffers under the weight of its own intentions. You can feel it straining to be something more, but it fails to deliver on this promise. Unlike some of the other Oscar-contending films of 2023, I walked away from this one pleasantly surprised but not provoked.

Interstate 60 (2002; dir Bob Gale)

Recommended by friend-of-the-show Liberty (🥃)(🇨🇦), Interstate 60 is a fun, thoughtful road movie disguised as a trashy teen comedy.

The bulk of the film (which was written and directed by Back to the Future co-writer Bob Gale) follows James Marsden’s hunky protagonist’s journey along the enigmatic “Interstate 60”, a seemingly magical place where “the past, the present, the future, the what-ifs and maybes, the roads not taken, become all converged, get jumbled up.”

Along the way, he encounters a sequence of colourful characters that represent some internal personal conflict he’s going through (prepare for lots of “no way is *that* actor in this film” cameos).

The film has a sort of wide-eyed innocence that beguiles its somewhat arbitrary R-rating. This and its magical realism vibe (Is this real? Does it matter?) reminded me a bit of Tim Burton’s Big Fish.

The highlight is a scene in a town populated entirely by lawyers, which is used as a set-up for some great gags, including a Simpsons-esque visual bit about ambulance chasing.

It’s a fun movie and far more interesting than the laughably terrible poster implies.

The Lives of Others (2006; dir Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck)

Phwoar, this is a powerhouse of a movie. Set in communist East Germany, it tells the story of a pair of artists and lovers and the lonely Stasi agent assigned to spy on them.

It touches on so many interesting ideas, from the false objectivity of surveillance (making it a good companion piece to Coppola’s The Conversation) to the degree of sacrifice that is justified in the name of art.

The film hits the beats of a Cold War thriller but strips away the indulgences of the genre and emphasises character over thrills. When it comes to its lead three characters, it is refreshingly nuanced and non-judgmental. A.O Scott hit the nail on the head in his New York Times review:

“The suspense comes not only from the structure and pacing of the scenes, but also, more deeply, from the sense that even in an oppressive society, individuals are burdened with free will. You never know, from one moment to the next, what course any of the characters will choose.”

I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a darker cut of this sitting in a basement somewhere - towards the end, some of the sharp corners begin to get sanded away, and the resolution of the various plot lines gets a tad mechanical.

My favourite description of Lanthimos’ films came from Rogert Ebert.com’s Glenn Kenny: “I don’t like what I took as a simplistic, scab-picking nihilism inherent in his vision and I didn’t like his cinematic way of expressing it.”

DePalma is always good, Sisters is a fun watch. At times it borders on sci-fi nonsense but man can he direct a film. Never knew i needed so many split-screens in my life.

Nice -- so funny to see Interstate 60 among that group of films, haha

So very niche, but hey, I like it ¯\_(ツ)_/¯