Slow Down

Movies are training us not to pay attention

Raw dogging a movie without pausing or second-screening is becoming an endurance act. Like running a marathon or reading a book. Only psychopaths do that!

The Sad Decline of our Attention Spans has been much discussed. Usually, it’s The Phone’s Fault. Or something to do with late-stage capitalism. Whatever that means.

As far as cinema is concerned, this hang-wringing misses something. The call is coming from inside the house. Films themselves have been training us to pay less attention for over 50 years.

As a millennial, I’m predisposed to like my sourdough toasted, my coffee beans fresh, and my movies fast.

I came of film-watching age at the business end of a trend that had been accelerating since the 1960s. Declining shot lengths.

In 1930, the average shot length (ASL) of English language films was around 12 seconds. In 2014, it was around 2.5.

Before you ask, this isn’t just a product of superheroes or mindless action movies. Once you start noticing it, you see it everywhere. “Today, films are on average cut more rapidly than at any other time in U.S. studio filmmaking,” wrote David Bordwell in 2006. “Although action films tend to be cut at a scorching tempo, fast cutting governs all genres.”1

I can’t sit here with a straight face and claim that this is Disastrous for Cinema. I make no bones about liking fast-paced films. No one wants to sound like one of the crusty old Parisian critics who scoffed at Impressionism, or the squares who dismissed rock & roll as perverted folk music.

Anyway, isn’t this just a case of horses for courses? Sometimes, a pacy ASL is good. The rapid-fire editing of Oppenheimer (2023) gave it its propulsive quality. Other times, a slower style is better. The uneasy stillness of Scorsese’s Silence (2015) wouldn’t work without giving shots time to breathe.

But “it depends” is BORING. It’s also a little naive. Yes, rapid cutting can be an effective tool. But that doesn’t mean it’s harmless. Though it has an artistic function, its history hints at something a little more unsavoury…

If you’re enjoying Rough Cuts, please consider subscribing (it’s free!) I also have a Buy Me a Coffee page for the wealthy benefactors among you…

Fast cutting is nothing new. It had been a tool in filmmakers’ armouries since at least the 1920s. So, why did this technique gain momentum in the 1960s?

Television! Bordwell quotes Sydney Pollack:

“In television, you are always fighting for the viewers’ attention, because they watch in a lighted room, more often than not, with more than one person and all sorts of distractions.”

Sound familiar? Desperate to hold viewers’ fragile attention, TV directors adopted the stylistic flair of a defibrillator, delivering regular electric shocks to comatose viewers by rapidly cutting between shots. Don’t look away now! Look at this new shiny image!

As the boundary between TV and movies blurred, with cable and video extending the lifecycle of movies well beyond theatrical distribution, TV methods increasingly infiltrated film (see also: tight close-ups). By the 1990s, with commercials and music videos proving a handy little side-hustle for the big-name directors of the day, the fast-cutting style was effectively canonised.

Meanwhile, a smorgasbord of technological developments made cutting easier than ever. Smaller, portable cameras enabled filmmakers to get in and among the action from more simultaneous angles than ever before. Combined with tightening shooting schedules, this encouraged filmmakers to ‘cover,’ capturing as much footage as possible for editors to stitch together in post-production.2 In turn, editors were freed from the tyranny of the scissors and tape by digital tools, allowing them to slice and dice shots at the click of a mouse. A ‘we can rescue this in the edit’ mindset emerged, one that favoured getting as much as possible over getting precisely what was needed.

Bordwell quotes Pauline Kael, who dismisses the technique's laziness with characteristic ferocity.

“The scenes will be chopped up with reaction shots and close-ups to conceal the static camera setups and the faults in timing, in acting, in rhythm of performances,” said Kael. “Fast editing can be done for aesthetic purposes, but too much of it is done these days to cover up bad staging and shooting.” Its effect is to create an artificial sense of pace, one that's divorced from what is actually happening on the screen. It does not “relate to any larger conception,” instead it is merely “effective here and now, in itself.”

Artificial pace and forgiveness of sloppiness. Consider these the original sins of the fast-cutting revolution. Together, they serve the same purpose. Keeping us hooked, regardless of quality.

I’m not saying that watching the breathless Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022) is the same as browsing TikTok. But I am saying that they are on more of a continuum than we may like to admit.

After 30+ years of movies refreshing their images every three seconds, is it any surprise that we are so vulnerable to the delicious promise of the constantly changing smartphone screen, or the endless scroll, or any of the other Bad Scary Distractions we hear about every day?

The more we become accustomed to constant bombardment, the less we are interested in anything more contemplative. Attention is like a muscle; the more we exercise it, the better it becomes. This is why slower cinema is so important to a healthy, movie-appreciating physique. It is quite literally teaching you to pay attention.

Buckle in, as things are about to get nerdy(er).

Imagine a conversation between two people sitting opposite each other at a table. They both look calm and collected.

In one version of the scene, it cuts to a close-up of one of their hands rapidly tapping his knee under the table.

In another, it doesn’t. If we look closely, we can see it at the bottom of the frame, slightly out of focus, but it could easily be missed.

In each case, who is in control of our attention?

A cut within a scene is, in essence, an act of narration by a film’s director. They are interrupting the scene to say “LOOK OVER HERE!” or “THIS IS IMPORTANT!” or, in the above example, “THIS PERSON IS NERVOUS!”

Fast cutting often means a more self-aware film. The director is frequently telling you where to look. What to think about.

One way to appreciate slow cinema, then, is to adopt the patented Stroppy Toddler Defence: “I don’t wanna be told what to do!” Longer shots trust you to make the connections yourself. “Accordingly,” says Bordwell, “directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail.”

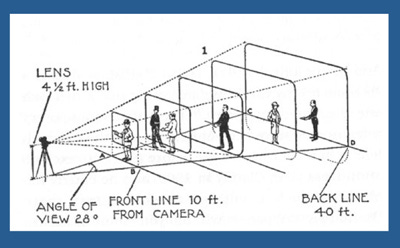

The basic geometry of cinema bears this out. Check out this pyramid:

Do you see what’s going on here? “Cinematic space–the space captured by the camera–constitutes a pyramid, extending narrowly away from the lens, and so it favors depth, “ writes Bordwell. “Accordingly, a film can have staging in depth that wouldn’t work onstage.”

In other words, part of what makes cinema unique is its depth of composition. There can be multiple elements in the frame that are not equally important to the action. Maybe something will be seeded in the background that will later become primary. Perhaps it is a small detail that enriches characterisation.3

Fast-cutting kills the sense of discovery inherent in longer takes. There is little room for discovery within the shot if it cuts within three seconds. There is no sense of earned satisfaction if the director flamboyantly points to a subtle piece of texture. Besides, if the film has been cobbled together in the editing room, then chances are the staging isn’t imaginative enough to plant the seeds of discovery anyway.

Back to Pauline Kael:

“And you are cued to react, you’re kept so busy reacting you may not even notice that there’s nothing on the screen for your eye to linger on, no distances, no action in the background, no sense of life or landscape mingling with the foreground action. It’s all in the foreground, put there for you to grasp at once.”

We can’t help but be accustomed to what we’re used to. Here lies the ultimate danger of the fast-cutting revolution.

Watching a slow film is not like eating vegetables, but if we only eat fast food, it sure feels like it. We become so accustomed to that fatty, salty taste that we lose our palate for something different.

In these circumstances, boredom becomes a perfectly natural response to encountering something that is, quite literally, slower than what we are used to.

The secret is to lean into the boredom. We can outsmart it! Fuck boredom! If it’s a well-made film and we’re bored, chances are, we’re not paying enough attention. We’re not noticing things. It’s not them, it’s us.

If you've enjoyed my work and would like to support it, please consider buying me a 'coffee.' If you haven’t enjoyed it, what are you still doing here! Go outside!

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes are from The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006) by David Bordwell.

Case in point: Mission: Impossible- The Final Reckoning, where Chris McQuarrie proudly describes his process of tucking into a “library” of contextless Tom Cruise reaction shots to retrofit into a stitched-together plot.

I think these points are largely right. But I have to HOT TAKE a theory of my own. I think one of the problems is that people don't like people anymore.

We're used to looking away from people, avoiding the gaze, fearing objectification or worse. Eye contact is now "strange" to younger people. And Movies have responded by de-empahsizing the face and the body. You rarely see an appreciation onscreen of how the body moves, unless it's killing people (and in those cases, effects ensure you don't get a great look at the face anyway).

I think a lot of this has been supercharged by directors and editors so in love with their visuals that they're dismissive, even disdainful, of actors (and studios have encouraged this so they depend less on "movie stars"). I do think people WANT to look at faces, they WANT to linger on someone's physicality. We should let them do this. We should like people again.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com

Fascinating stuff here, Ed; thank you for this!

Delighted that you mentioned the editing of Oppenheimer here; not only does the fast cutting offer a sense of propulsion, as you put it, but the overwhelming majority of those cuts occur whenever a character is in the middle of an action or a movement. Combine this with its non-chronological narrative - where moments in time itself are liberally plucked from the continuum as needed for the story - and the film echoes the perpetual motion of the very atoms that Oppenheimer leveraged in his work.

And whenever a cut is made on a more restful note? What does that say about the ceiling of human progress and capability, both collectively and individually, scientifically and emotionally? What do we do when our own motion turns out to be very much not perpetual?